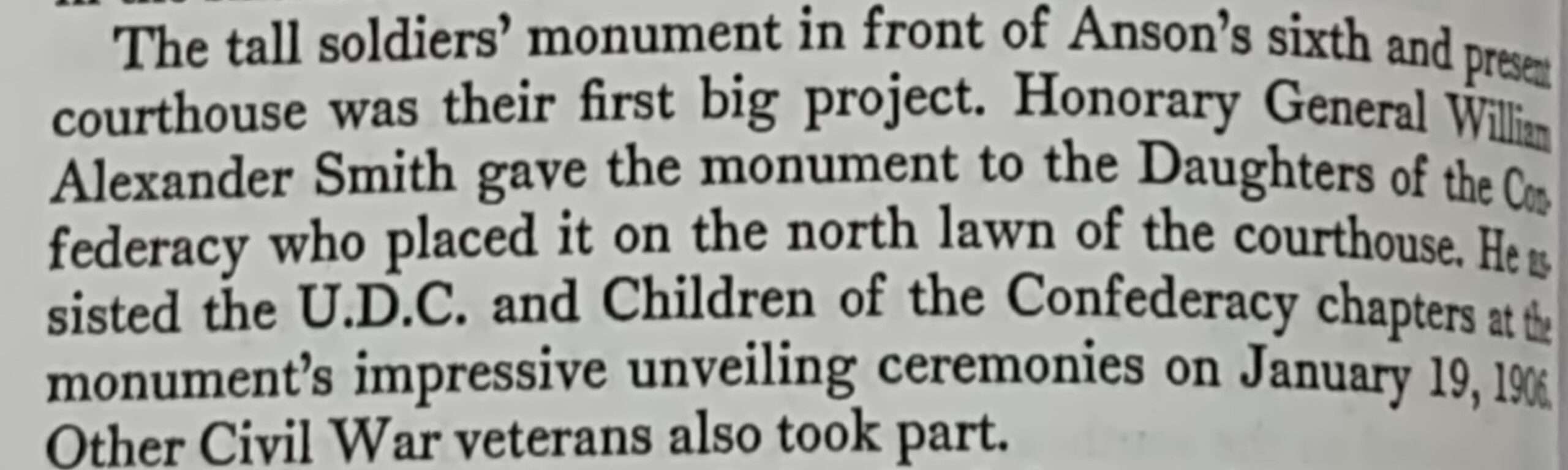

As you can see in the Anson Record article posted on Causes: Lost & Found, there is a common misconception regarding the Confederate soldiers’ monument being provided BY the United Daughters of the Confederacy. The Honorary General William Alexander Smith was a wealthy Anson County Freemason that gave to his community in life and is credited with much greater generosity in death. In fact, we should know more on the extent in 2033. That my calculation on the end of the 99 year term specified in his will for a fund to be managed by three trustees over that time. It is directed to be paid to the Episcopal Diocese of North Carolina at the conclusion of the 99 year term.

WUNC | By Mitchell Northam

Similar to the article posted on Causes: Lost & Found, the article above also credits the purchase to the UDC. It also says that the soldier is at rest, but this is obviously not a resting position. This is Order Arms (Attention) with a much lengthier long rifle. His hands are a his sides, there is minmi

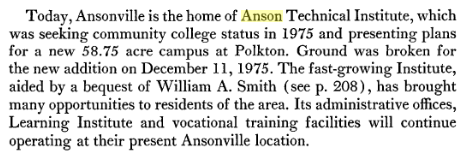

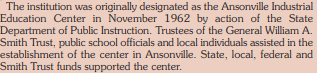

I mentioned on ‘How Time Works‘ that slight changes have been made to accounts in order to fit the desired narrative. Let me provide an example. The photo below is from a book by Mary Medley, ‘History of Anson County North Carolina 1750-1976.’ I’ve enjoyed reading this book (several times), but there are some parts that are not accurate or completely omitted. See example below:

We all know that isn’t true now, so what can you actually trust from the rest of the book? I will say that I wouldn’t trust much in either of the two books by Smith.

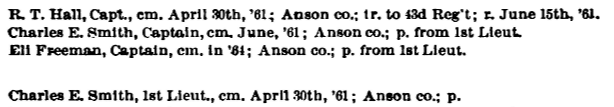

It appears the Commemorative Landscapes profile has greatly influenced the erroneous belief that the UDC purchased and provided the Confederate soldiers’ monument in Wadesboro.

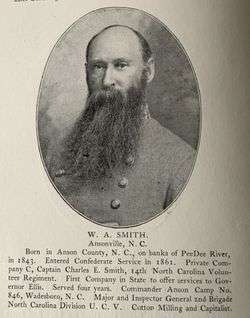

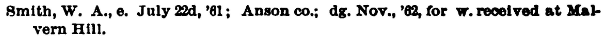

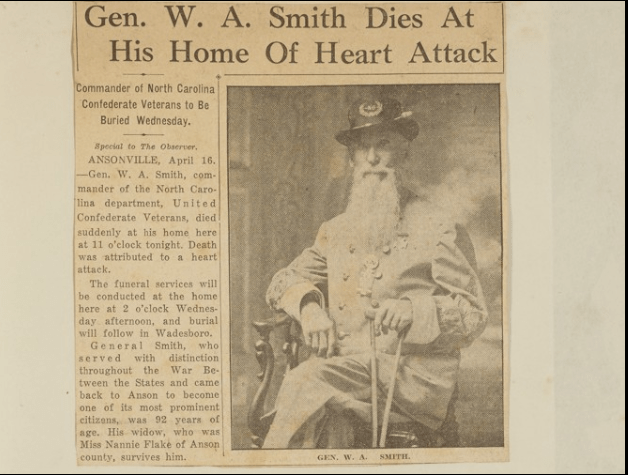

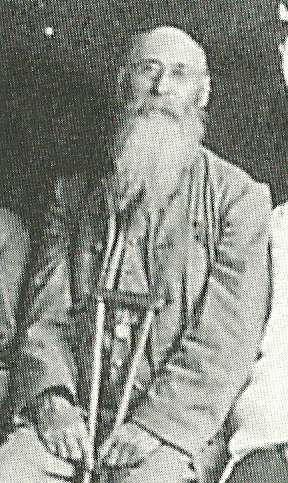

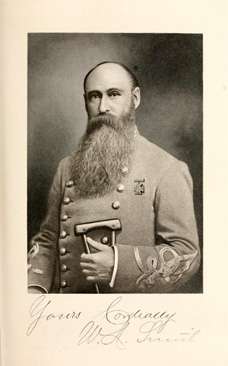

Smith came from a family of wealth and military (at least militia) leadership. He attended Davidson College until enlisting inn the Confederate army on July 22,1861. This enlistment is reported to have interrupted and brought an early end to his sophomore year. I’ve read that he felt compelled to serve because he came from “soldierly stock” on both sides of his family. His enlistment is recorded as almost three months after his brother and E. Fenton (mentioned below). Records state that he was wounded in the leg on July 1, 1862 at the Battle of Malvern Hill (or Battle of Poindexter’s Farm) as a Private in the color guard. The Battle of Malvern Hill was fought near Richmond, VA. “This was his first and last battle” of the Civil War, even though some sources mention his continued service throughout the war. See photo to the left. In Smith’s ‘The Anson Guards,’ a telling of the events at Seven Pines, Williamsburg, and Yorktown portrays that Company C didn’t act in battle until Malvern Hilll. It also vaguely alludes to Smith’s assignment, then picks up with the end results of the battle. More specifics are given on end-state than setting or battle explanations.

Below is a quote from a piece written about Smith:

“The writer of this picked up the bloody and desperately wounded boy lying nearest the enemies’ guns, faint from the loss of blood and without murmur or groan, we bore him to the rear. We never left his side until placed in the tender care of his loving and praying mother. For six months Major Smith hovered between life and death. The devotion and careful nursing, and the prayers of his Christian mother at length prevailed and the beardless boy’s life was spared to the world, but the wound received at Malvern Hill has made him a cripple for life.”

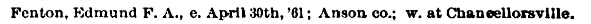

Edmund F. Fenton, a private of Company C of the Fourteenth Regiment

I find it peculiar in a time before antibiotics with such a serious wound that he was only crippled and did not lose his leg, but not all became amputees. Smith’s friend Fenton did. His brother, Charles E. Smith, was also apparently a Captain in the same company; however, it’s claimed that Charles declined re-election as Captain when the companies reorganized at Yorktown in April, 1862. In W.A. Smith’s ‘The Anson Guards,’ Smith stated that it was due to his failing health. It is said that C. Smith then went back to Anson County and farmed for a few years before moving to Tennessee for a new start. The ‘Anson Guards’ had not yet faced the enemy until this point in the war when they were positioned along the Warwick River in a show of force.

As for Fenton’s account above, I’m not certain how much we should trust his word either. Col. Risden Bennett wrote in Smith’s book ‘The Anson Guards,’ “Under their roof Major Smith, our special guest, friend and helpmeet, resisted disease, while Dr. Tucker came to his hurts – probed them and made his hurts tolerable. I wish the people knew how much Major Smith suffered for the cause.” It seems Smith was transported to Captain / Councilman Thomas C. Epps’ private home at 20 East Baker Street in Richmond, and stayed there until November of 1862 when he was discharged from service (see record posted above). The ‘Epps Hospital’ was “used temporarily… for North Carolina troops in 1861 and 1862.”

At the time, Davidson offered no majors and there were prescribed courses for each year attending. I’ve been told it was more of a finishing school for landed gentry, as well. I did read where Davidson students learned Greek and Latin as part of the studies, and Smith wrote in a letter later in life that he struggled with Greek. After graduation from Davidson, he went into business with a partner opening a general store in Ansonville, eventually became sole proprietor, and worked at this for twenty years. Following retirement from this in 1886, he went into cotton textiles in Montgomery county and apparrently had great success in this. It’s claimed that he served as the president of both the Yadkin Falls Manufacturing Company and Eldorado Cotton Mills. Sources claim involvement with many other successful business ventures. It’s reported that he acted as an investor in many industries after his retirement from the cotton mills in 1905. It is claimed “banking, commercial finance, textiles, insurance, real estate, tobacco, furniture, transportation, patent medicines, electric power, the telephone, and the mining of gold, copper, and mica all were included in his portfolio.” One of his most notable investments was in American Trust Company at its formation, which eventually became Bank of America through several mergers. Smith also ‘operated’ a family plantation of 1,500 acres that he was able to either buy the other heirs of his family out of their inheritance to obtain or it was abandoned by others. His brother, Charles E. Smith, left his inheritance to the siblings that remained in Anson County with his move to Tennessee. It appears that W. Smith may have been one of two siblings to remain in Anson County. One moved to Rowan County, another to Forsyth, two sisters to Arkansas, a brother to Tennessee, and one sister that may have stayed within the county. She also might have married into her own wealth, though. The plantatation was maintained by tenant farmers, and this was enough to “warrant appointment by the governor as a delegate to the Farmers’ National Congress held at Sioux Falls, S.Dak.” His father had inherited a “handsome” property from his father and they were obviously a family from old money. The line below was written about the brother Charles, but it stands to reason the same would apply to W. Smith due to the relation.

“He was the pure product of fortunate birth and prosperous circumstances.“

Wounded in July 1862, spend six months hovering “between life and death,” finish his sophomore year and on at Davidson, and then graduate in 1865 doesn’t fit into the story later told. Once again, that’s not how time works considering the war ended on April 9, 1865. You can’t be in two places at once. Either he was serving “with distinction” throughout the war until April 1865, or he was attending Davidson for the remaining years and graduated in 1865. Davidson lists him as an 1865 graduate, and records show his discharge from service in November of 1862 due to wounds sustained at Malvern Hill. The facts don’t line up with the fictional narrative he fabricated for his life.

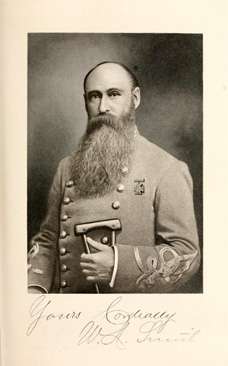

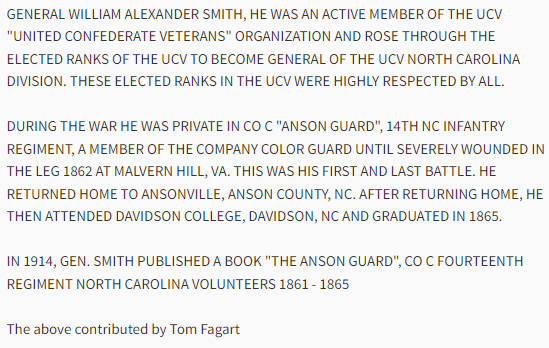

Smith was very involved with the organization of the United Confederate Veterans and was elected to the rank of Honorary General and commander of the North Carolina veterans. He would reportedly have annual spring reunions of Confederate veterans at his home, The Oaks, in Ansonville, NC. It appears he gained great fame during his time with the UCV, even with his limited service during the war. I believe the inability to verify service details during the war led to much of his rise through the ranks of the UCV. It appears that his wife’s family may have played a part in his UCV advancement too. He succeeded his brother-in-law as the commander of the Anson Camp, UCV. He later became the commander-in-chief of the North Carolina Division of Confederate Veterans and was honored at events he attended.

The photo of Smith above is in the Library of Congress. The button attached says ‘First at Bethel / Last at Appomattox,’ The full saying was, “First at Bethel, Farthest to the Front at Gettysburg and Chickamauga, and Last at Appomattox.” It was a saying that honored North Carolina veterans and boasts their experiences during the war.

With his actual service in the Confederate army being what it was, I’m not certain others knew his true story. I think the report stating “the cause of the Confederacy has always been the closest thing to his heart” may have been the deciding factor that elevated him. He was also a enormously wealthy, a wounded (Confederate) veteran and unlikely to be questioned. He was intelligent enough to understand his name attached to the soldiers’ monument would give away more of the true intent of the monument. A soldiers’ monument would be much better perceived if it came from women as a place to lay their flowers in memory. If there were a monument honoring the women, his name would likely be conspicuously attached.

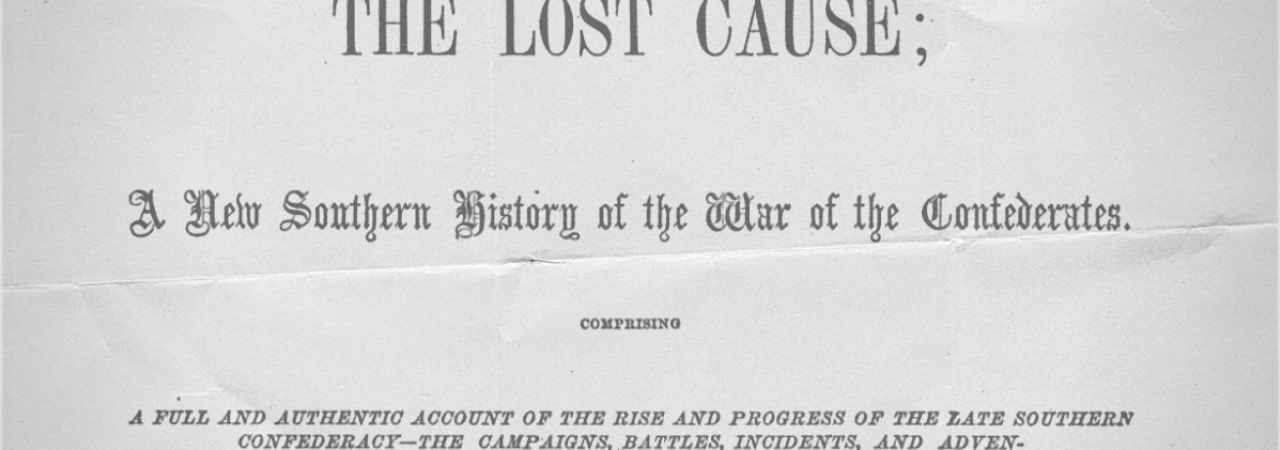

The cause closest to his heart has to be the “pure cause” mentioned in the poem. The cause mentioned in the poem, and other places, is undoubtedly the Lost Cause meant to justify and glorify secession and the Confederacy. The ‘Lost Cause’ is a cause of white supremacy.

W.A. Smith may not have been of sound mind the final eight years of his life. A claim that he was cared for by legal guardians has been discovered recently and is being further investigated. “Mary (Bennett) Smith, William Alexander Smith’s wife, and Bennett Dunlap Nelme, who, after 1926, were the legal guardians of William Alexander Smith.” This is highly unusual due to Mary Bennett Smith passing in 1914.

I can only imagine how resistant I would be to allow someone to become my LEGAL guardian, so I can see the process taking some time before going into effect by 1926. It begs the questions of when the legal guardianship was first initiated, and what was the cause of Smith to be determined legally incapacitated. “He wears the Confederate uniform on all occasions” is a line from the article above that struck me as odd on the first read. That was long before ever seeing anything about a legal guardianship in his final years.

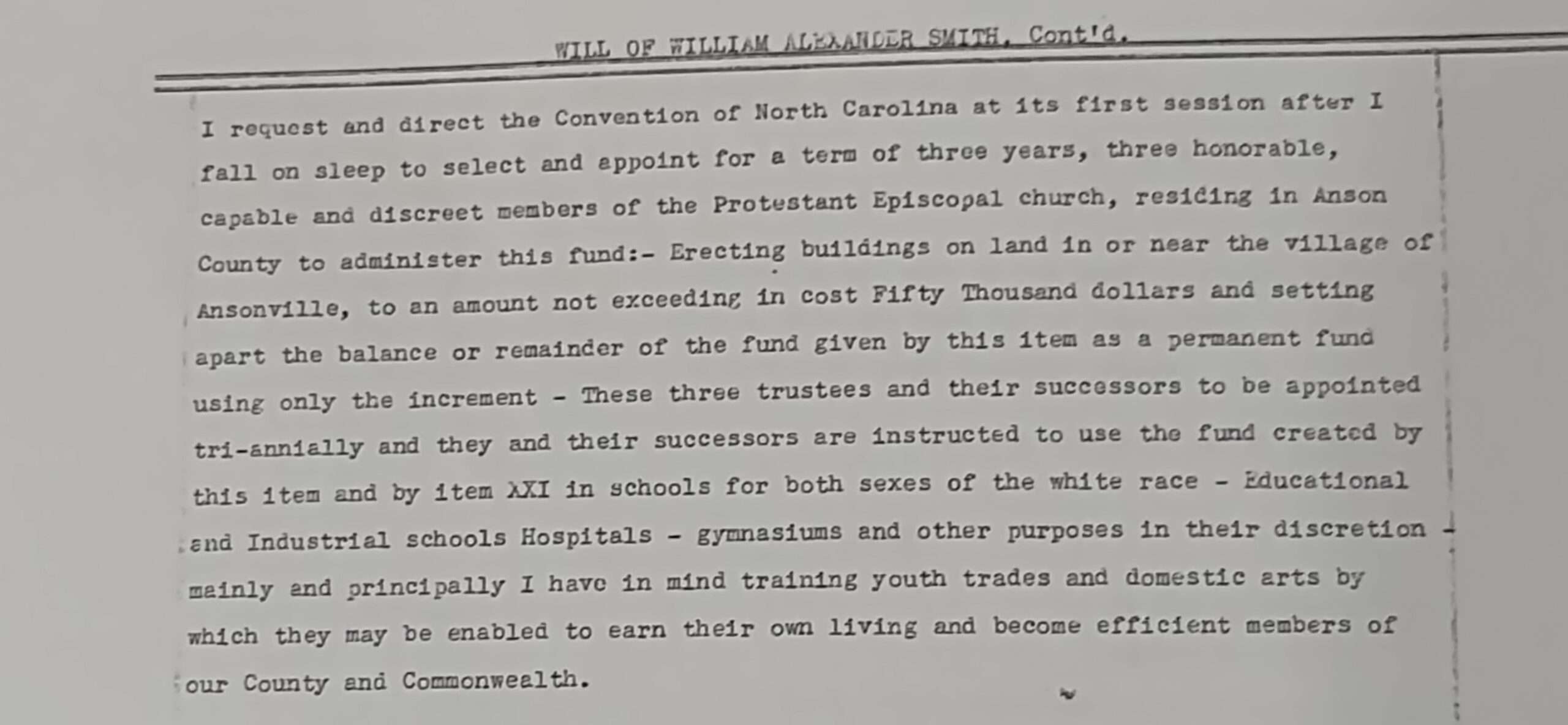

We can be certain that Smith’s true intent (not another fabrication) was that of the Lost Cause when reading his will; confirmed specifically by items XXI and XXII of his will. This is where the 99 year fund is created.

“This fund is committed to said Bank of Wadesboro and its successors for the period of ninety nine years, it and its accumulations to be paid to the Diocese of North Carolina at the expiration of said 99 years.”

“I give to the Diocese of North Carolina as named in item XXI of this Will, the remainder of my estate both real and personal, to be used primarily for the benefit of my race – for the purposes as set down below.”

This section seems clear on who Smith desired benefit from his bequest, but there is additional clarity provided as you read item XXII.

“These three trustees and their successors to be appointed tri-annially and they and their successors are instructed to use the fund created by this item and by item XXI in schools for both sexes of the white race“

In April 1934:

The article above has two inaccuracies that caught my eye. Smith was actually only 91 at his death, born January 11, 1843. I have previously covered the impossibility of serving “with distinction” throughout the Civil War AND completing his studies at Davidson over the same period of time. There are also records.

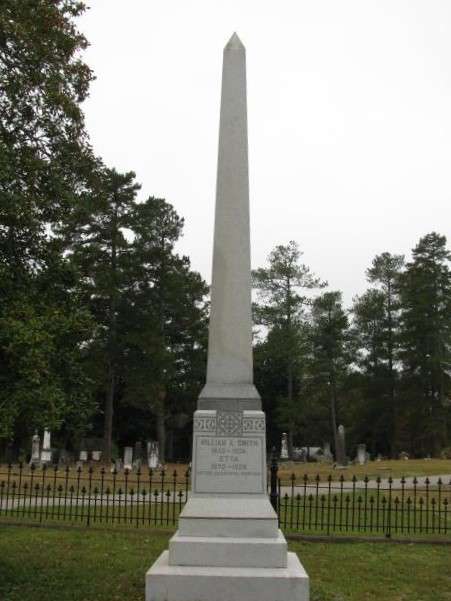

As a wealthy Mason would have it, his grave in Wadesboro’s Eastview Cemetery is marked with an obelisk:

The image above is from Mary Medley’s book mentioned at the top of this page shows that a sizeable portion of his money went to education, just that it was meant to educate only the white population. Against his wishes, he has assisted in educating many people of ALL races. Of course, Anson County was slow to integrate its schools and the school underwent a name change with operational changes in 1967 to become a unit of the Department of Community Colleges of North Carolina. This was around the time that integration became a much larger issue in the county.

What if Smith, like the rest of his life, didn’t really do that?

Medley also included an incorrect birthdate for Smith in her book on Anson County:

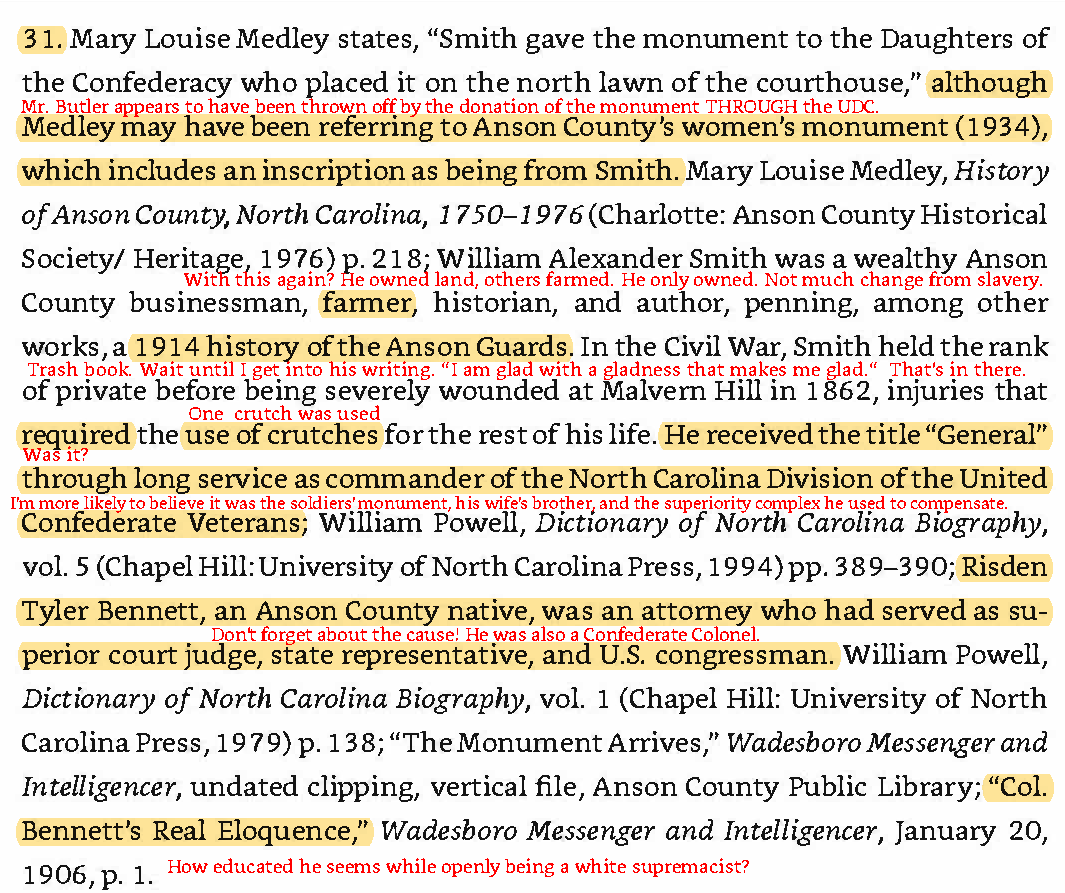

Below is a section of Butler’s North Carolina Civil War Monuments, An Illustrated History with comments:

The Oaks

Please take notice of the crutch (as he no doubt intended) conspicously placed in near the same position in each photograph. The crutch makes an appearance in every photograph of Smith, regardless of if that photograph is a full-length body shot or not. I haven’t uncovered any antebellum photgraphs of Smith in my investigation.

CLICK HERE to read more about the Lost Cause

Item X of the will provided something else for the county:

“I direct my Executor to erect a monument on the Court House lot in Wadesboro, N.C. at a cost of $2000, not to exceed three thousand dollars to my mother Eliza Sydnor Smith, to my wife Mary Bennett Smith, naming them on said monument, and to the women of the Confederacy.”

Please DO NOT tear down any of these monuments after reading these pages!!!!!!!!

The United Daughters of the Confederacy or the Sons of the Confederacy, depending on the monument, have insurance policies covering these monuments for exorbitant amounts. Removing these monuments in any way but a lawful one will only make them stronger.

CLICK HERE to see the product of Item X.